Industrial Design Process for the ‘Time Sense’ Prototype

The first silicon-based “dummy” wearable for cyborg Neil Harbisson’s “Time Sense” prototype is now ready, and Neil has been testing it for comfort and fit.

In this post, I’m going to talk about the industrial design process undertaken on this project, from design to deployment of the first silicon wearable.

Our goal is to create a permanently-wearable ‘soft device’ that allows Neil to feel the sensation of time passing throughout the day, as a micro-heat sensation around the circumference of his head. In the development of any cyborg sense, the initial goal is always to create a comfortable wearable with embedded electronics, including sensors or actuators that the cyborgs can actually feel.

These wearables allow the cyborgs to actually experience a new prototypical sense, so they can learn about what works and what doesn’t before developing it further. Based on that experience, they can decide what direction to go next, including potentially developing implants that will become integrated into the human, merging technology and biology.

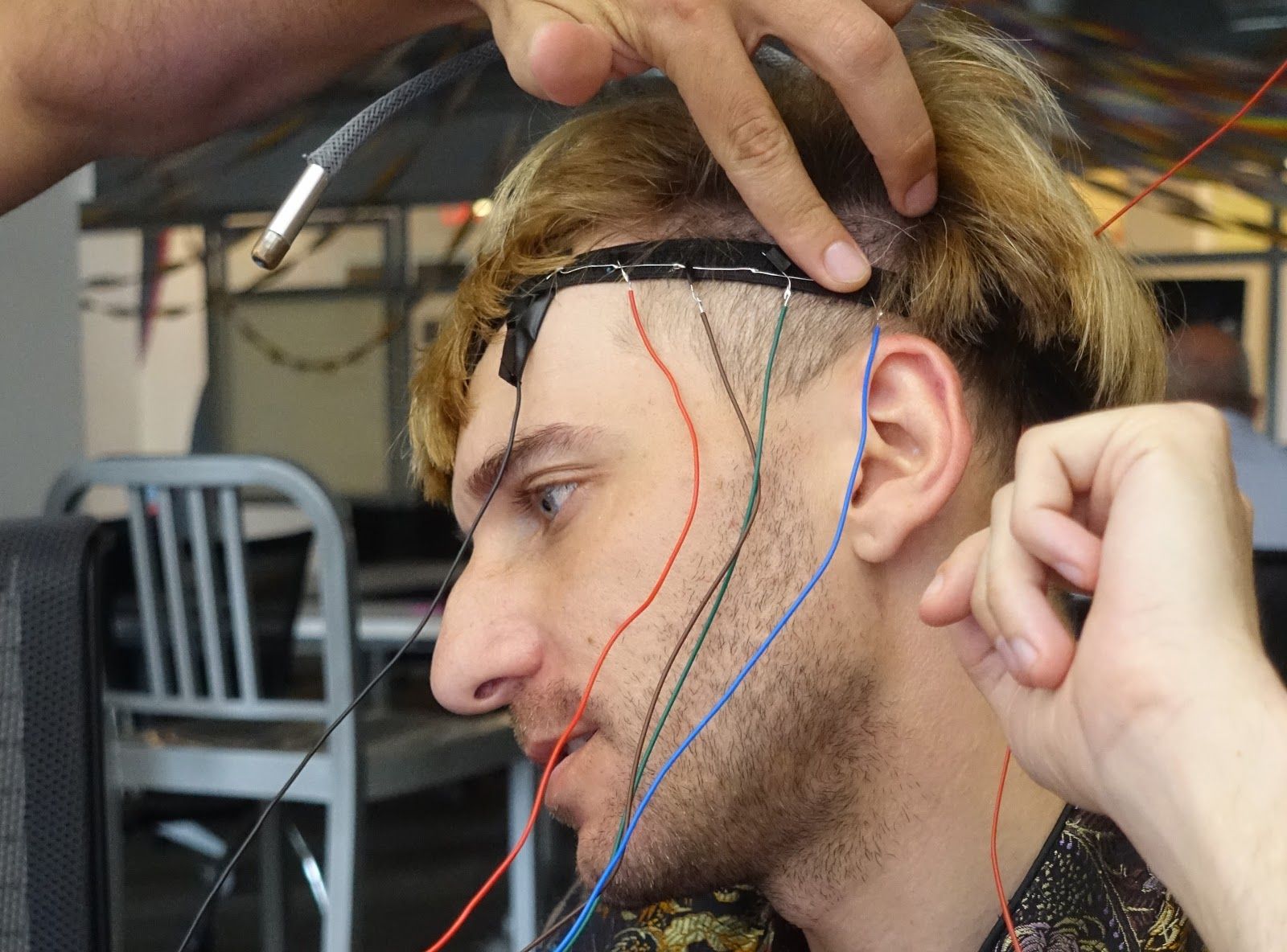

The first part of this ‘wearable prototyping’ stage was a functional proof of concept, shown above, which we created during the Cyborg Foundation’s residency at Thoughtworks in the summer of 2016.

I am now working on the next stage — creating a durable physical wearable, in which to combine new, miniature electronics with a unique industrial design, thereby creating a smoother user experience for the cyborgs.

3D Model and Dummy Wearable

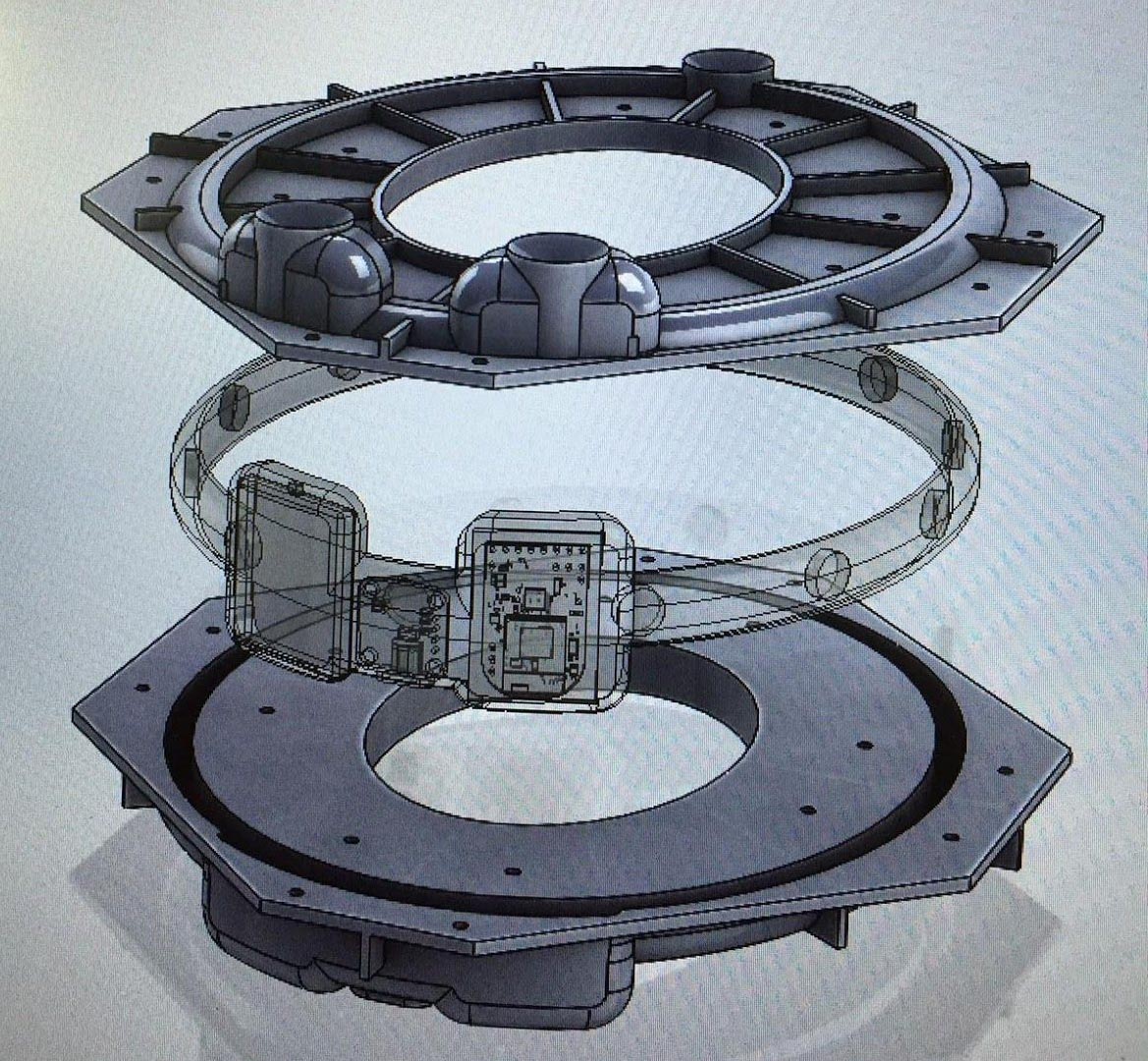

To begin the process of creating the durable wearable, I created a 3D model of the prototype, shown in the picture below. The model incorporates miniature versions of the electronics from the functional proof of concept, along with materials chosen based on research by the ThoughtWorker Caihong Liu, based in Chengdu China, during the residency.

Next, based on the prototype model, I created a 3D virtual two-part mold from which the wearable could ultimately be cast.

The holes in both parts seen in the picture below are for bolting the parts together, known as ‘mating’ the parts, when injecting the silicone into the negative space in between.

This empty space will also contain the electronics when injecting the silicone in the final version.

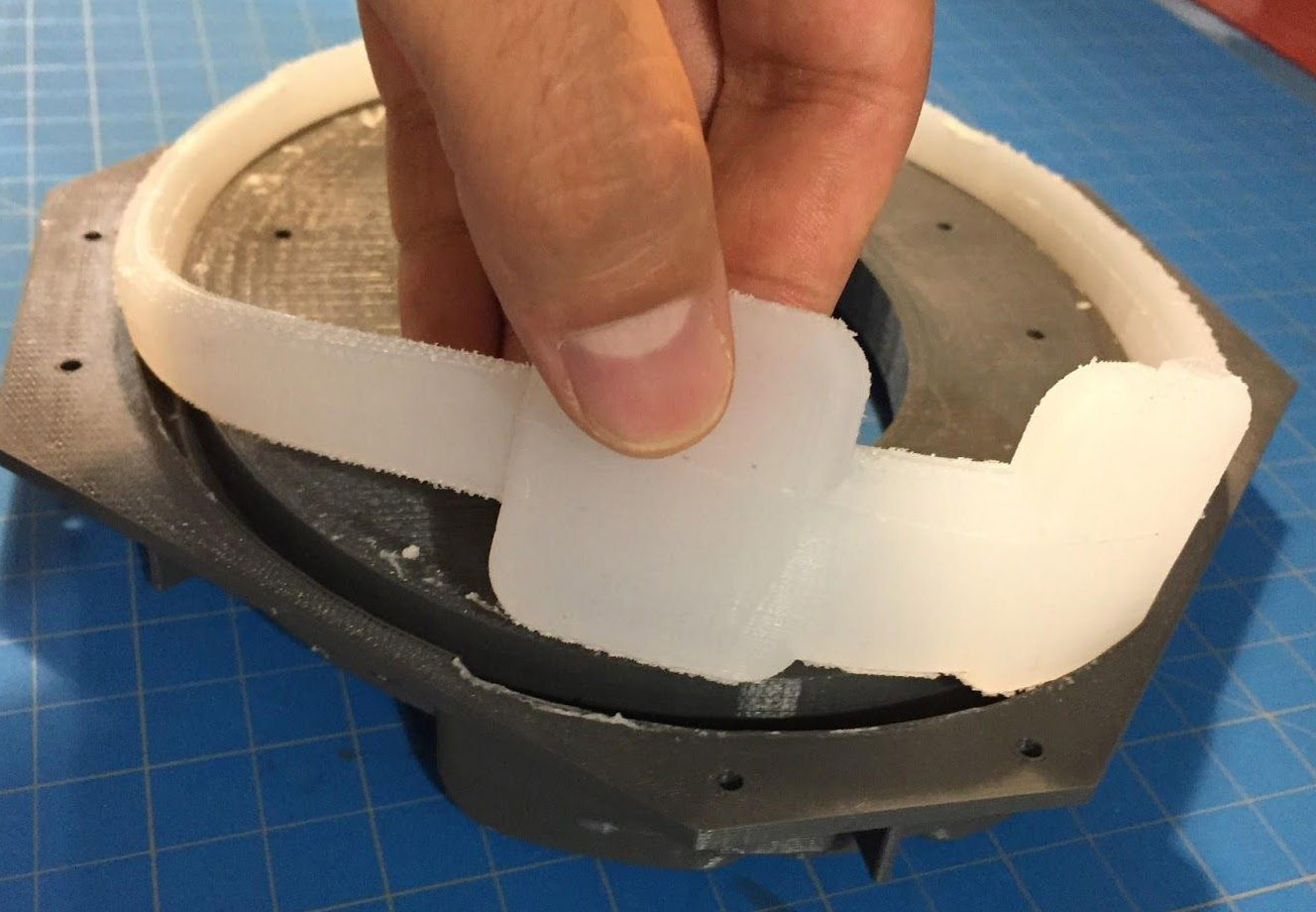

Next, I produced a “dummy” physical wearable based on that 3D model, which does not contain electronics. This version of the wearable gives Neil his first chance to try on and report back so we can make design adjustments before moving towards a final design.

In this initial test round, Neil is reporting specifically on comfort of the physical headband. This is highly important, because Neil intends to wear the completed headband 24 hours a day, seven days a week, as part of his process toward considering developing an implant sometime in the future.

Producing the Headband

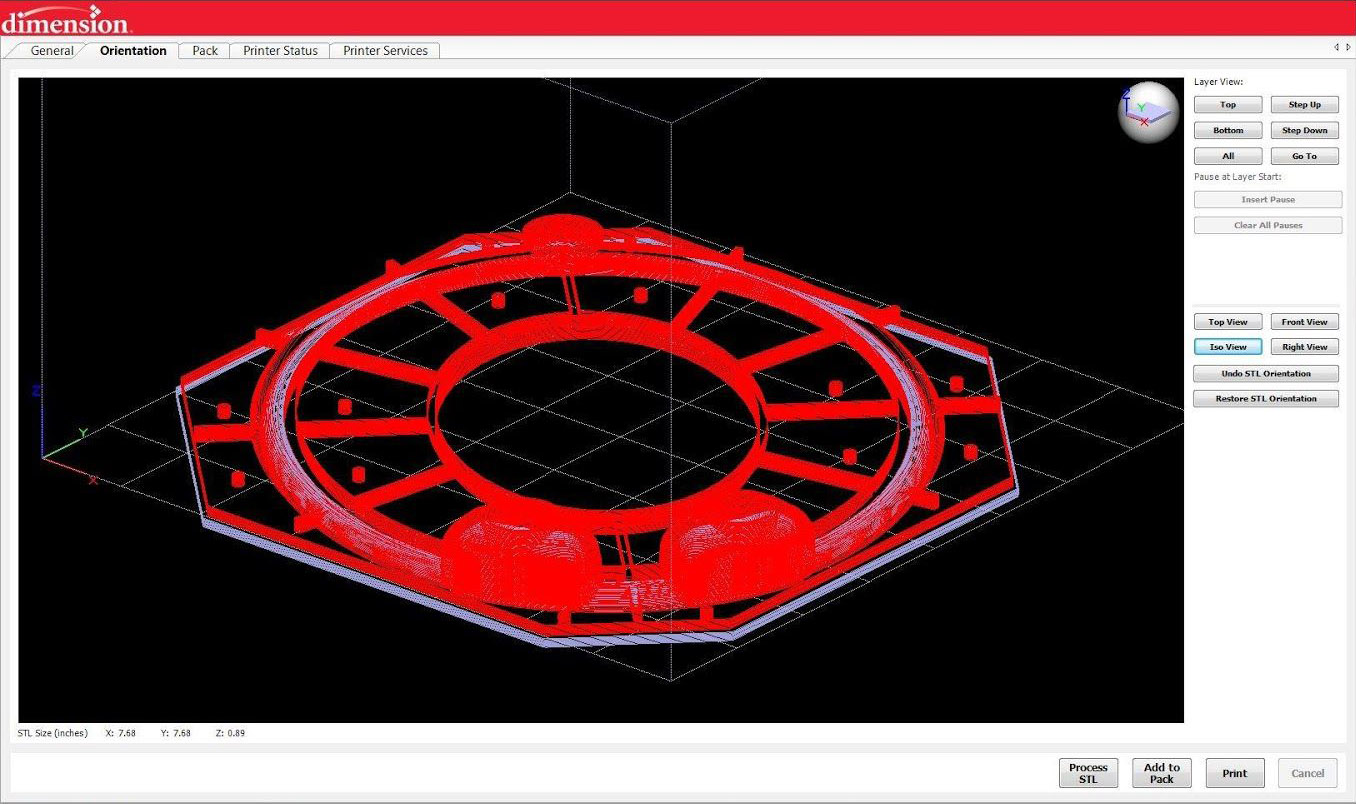

As shown in the image above, the first stage in creating the dummy wearable was to 3D print the two-part mold. The main material used to print the mold is ABS (Acrylonitrile-Butadiene-Styrene).

Another material, HIPS (High Impact Polystyrene), is used as a support material, allowing me to print shapes with overhanging features. The HIPS holds these elements in place during printing and cooling. The HIPS is then removed after printing, leaving the overhanging shapes intact.

The HIPS support material was removed by submerging the complete final print into a limonene solution, which dissolves HIPS without affecting the ABS.

Next, the two molds were sanded to smooth out the surfaces ready for mating. The tighter the mating is, the less silicone will squeeze out when the two mold parts are connected, thus creating a better werable in the end.

A secondary treatment for this typically uses acetone vapor, which is very caustic on the plastic and if done right can produce high smoothness with little loss of detail. However, that level of aesthetic treatment was beyond the scope of this first iteration and so was skipped.

The silicone material chosen for the actual wearable was then mixed, and the solution placed inside a vacuum chamber to extract any bubbles that may have formed. The silicon was injected into the mold, and the mold and silicone together took another turn in the vacuum chamber to further reduce bubbling.

Once the silicone had set, the mold could be carefully removed, and the wearable extracted ready for testing.

Testing the Fit

Given that this was our first run, I expected that the dummy wearable might be too tight or too loose. However, in testing, Neil reported wearing it for several days without discomfort.

I explained to him that the flexibility of the headband would be somewhat reduced with the introduction of the electrical components inside it.

We are now planning to refine the 3D model, print a new version of the headband, and move forward with the electronics. Specifically, we will cast the individual heat elements through which Neil will sense time, and then solder the wires and electrical components from the design and embed them in the new headband.

Keep on top of Thoughtworks Arts updates and articles: