Cyborg Senses: Weaving the Materials

I never knew that one day I would be part of a project to develop new human senses — but here I am. I’ve spent the last six months working with the Cyborg Foundation on their Thoughtworks Arts Residency project.

In this post I want to explain what I learned about materials and wearable devices, in the context of experimental new forms of human-computer interaction.

A quick primer

The project is composed of two parts, both intensely fascinating. Neil Harbisson aims to create a new sense of time, in which he will feel the passing moments of the 24-hour clock as a continuous heat sensation traveling the circumference of his head.

At the same time, Moon Ribas intends to develop a new sense of planetary motion for her feet, in which she will feel real-time global earthquake activity. This will give her a sense of how intense and far away from her the seismic shocks are.

During our early planning meetings, I decided that the subject where I could contribute the most was materials research. These senses would require electronics on the body, and those electronics would need to be housed in some form of skin-safe material.

Going in the wrong direction

Sometimes there are misunderstandings, and sometimes there are mistakes. They are especially likely on a highly experimental project, stretched across global time-zones, in which participants are communicating in their second language.

Neil and Moon both already have permanent subdermal implants. They contend that this is what makes them true ‘cyborgs’. Dialing in for planning meetings from Chengdu, China, I originally understood “exoskeleton” to mean “still subdermal” — below the skin.

In fact the intention during the residency was to make wearable prototypes for evaluation. Neil and Moon intend to try out these wearables as semi-permanent senses, and may consider making permanent implants going forward.

With this clarification understood, I began digging into wearable-style materials research.

Special effects silicones

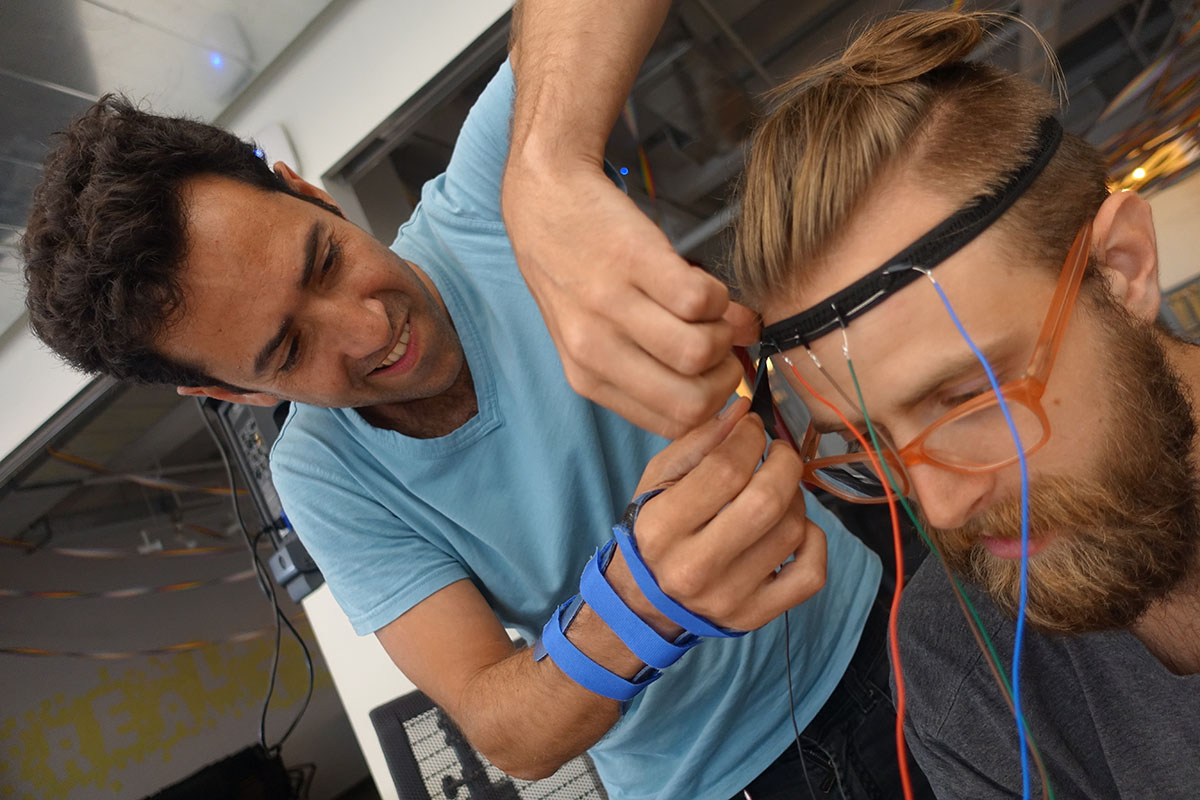

One of our project team, industrial designer Oryan Inbar had experience using special effects silicones previously, and we collaborated closely to validate my research with product samples.

Our first investigations were into a silicone called Skin Tite / Thi-Vex. Unfortunately, this material can get tacky after some time. We discovered with practice that it would not be able to hold Neil’s sensor, as it would mess up Neil’s beautiful hair.

Another material we discovered is Smooth On’s Dragon Skin, which is much stronger. Although these two materials are commonly used for skin special effects in movies, I could not find the data proving that long-term wearing would still be skin and human safe, as this is not in the nature of their intended use.

For this reason, we ruled the special effects silicones out and continued research into other areas.

Synthetic fabrics

Moving forward, we decided that perhaps we should give fabrics a try. I did some research into the properties the synthetic fiber Spandex, and the synthetic rubber Neoprene.

Using these fabrics we could conceivably make a head-band for Neil’s time sense with the sensor sewn into the band. We could also make Moon a pair of socks, again with the sensors sewn in.

However this research ended up highlighting the importance of a key criterion for the wearable — that it protect the electronics from water damage. When it rains, or when Neil and Moon decide to go swimming, for that matter, the sensors and electronics would not be protected by these synthetic materials.

Increased fabric density or intensity could compensate. However this would lead to issues with wearability, and also would have a negative effect on the functioning of the embedded sensors and actuators. With more fabric material to pass through, actuators would need to draw more power to have the same effect, and this would shorten the battery life of the wearable.

In addition, a key point for Neil and Moon is that they be able to wear these wearables constantly, day and night, and for months at a time. This is part of what makes these prototypes “senses”, rather than simply wearables, and makes what Neil and Moon experience instinctive “feelings”, rather than just notifications.

Hypoallergenic metals

Further research led me to hypoallergenic metals, which are popularly used in jewelry and fashion. I considered that we could customize a product like this into a head ring for Neil’s time sense, with the actuators welded or glued to the outside the ring.

In addition to that, we could customize a product like this into toe rings, for Moon’s geographic seismic sense. In this case, the actuator could be welded or glued on top of the ring.

However, this option has it’s own drawbacks. The rings would have to be re-sized to match the size of the sensors and actuators, which might change over several iterations. Additionally, it could cause comfort problems for Moon in wearing shoes. As a dancer, Moon values movement of her feet very highly.

Possibly the worst drawback of this option would be the look and feel. Hypoallergenic metals would likely not attach to skin in a beautiful way, so ultimately I discarded this direction of research.

Epidermal electronics

Another consideration was using the skin itself to shape a stretchable electronic circuit. The area of research known as epidermal electronics is a fascinating approach in which sensors can behave like tattoos, printed directly onto skin.

Alternatively, stretchable electronics can be applied to the skin with adhesive patches, for example the commercially-available MC10 BioStamp.

This direction looks fascinating, however due to the additional constraints it would apply to the circuitry, epidermal electronics should only be considered after you have a proof of concept and are ready to miniaturize.

Digging deeper into silicones

There are a great number of silicone options available out there. I decided to dig deeper into silicone, because of it’s inherent softness, water-proof and abrasion-proof features.

Oryan and I considered RTV Silicone Rubber, a food grade silicone. We discovered that it is made and cured at room temperature, and that once cured it is soft and elastic. We also looked at NuSil, a medical grade silicone, manufactured and purified to meet the strict requirements of the healthcare industry.

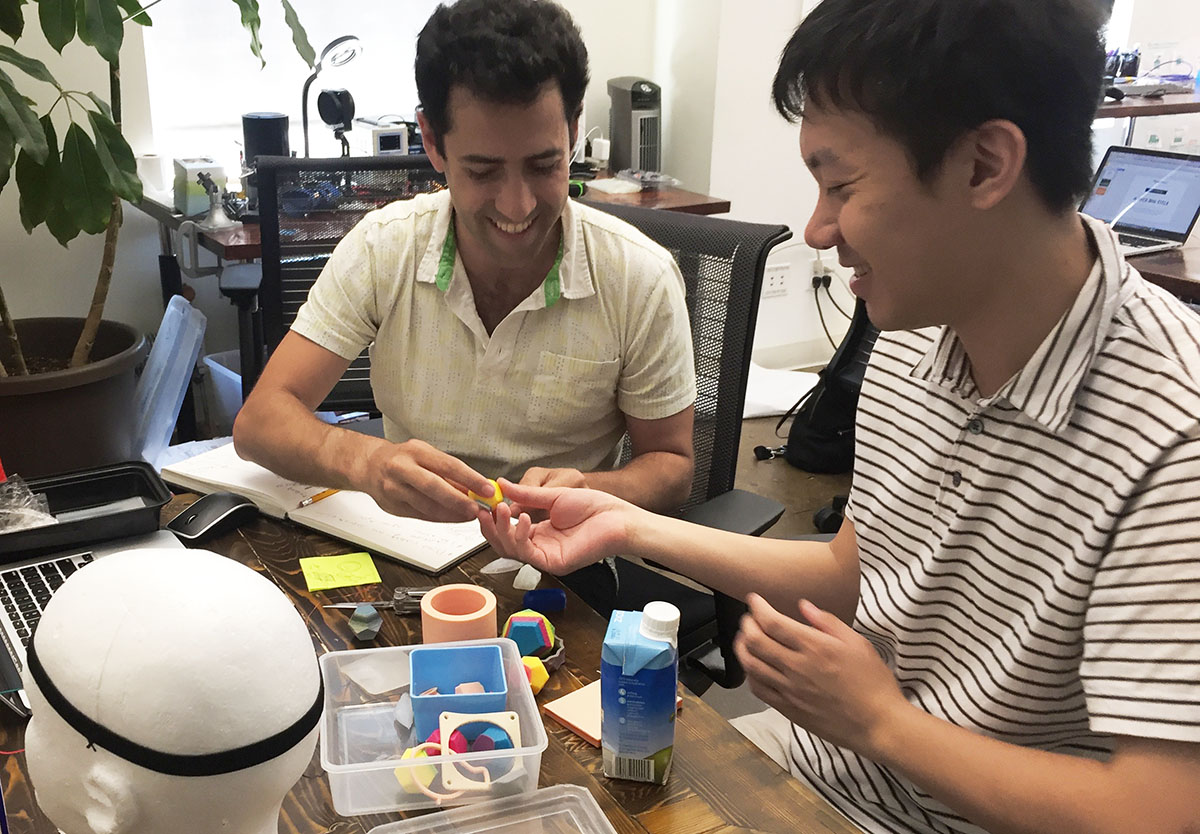

Finally we discovered San Draw, a 3D-printing company which has been refining it’s silicone manufacturing process in an effort to target the medical industry. San Draw’s patent-pending 3D printing technology enables printing of full-color objects with adjustable hardness.

Oryan Inbar contacted San Draw’s CEO, Gary Chang, and was able to arrange an in-person meeting and demonstration. During the meeting, we discovered that not only was the San Draw product flexible enough to meet our needs, but that it was also skin-safe for extended periods of constant wearing.

Additionally, San Draw is soft, and water and abrasion proof, matching our criteria well. Discovering this seemingly perfect material and production process freed us to begin investigating another quirk of Neil’s headband design.

Transferring heat to Neil’s head

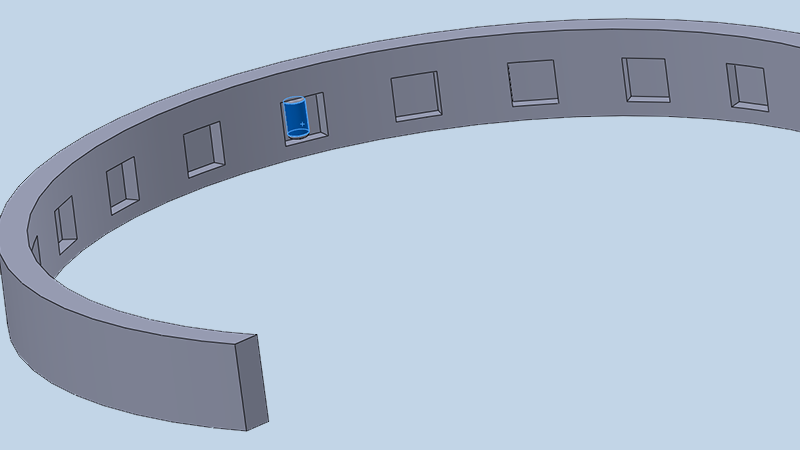

Although San Draw would make a good candidate for the band part of Neil’s wearable, we had one more materials concern to address. Neil’s band would contain a series of electronically-powered thermal sources distributed across the band, as shown in the image below.

In addition to the band material, we would need a coating material to sit between the thermal source and the skin, at the location of each thermal source.

This material would have an additional constraint — as well as being skin safe and electrically insulating, this material would need to be highly thermally conductive. The more this material masks the heat, the shorter the wearable’s battery life will be.

| Material | Thermally Conductive? | Electrical Insulation? | Skin safe? |

| ConductiveX | Yes | Yes | N/A |

| Epoxies | Yes | Yes | N/A |

| MasterSil 151AO | Yes | Yes | N/A |

| LORD Thermoset SC-104 | Yes | Yes | Food Grade, not directly proven as skin safe |

| MasterBond EP21AOLV-2Med | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Of the five options I discovered, MasterBond appears to be the best match for the requirements. I could not find another silicone which combines all three features together.

I raised concerns about the hardness of this epoxy. However, Oryan is confident it will work because the skin contact area of this part of the band will be so small.

A unique project

Taking part in such a unique project, distributed across such varied time-zones, has been a particular challenge. Crossover arts and technology projects like this one have such incredible potential to push new boundaries and pioneer new concepts and ideas.

My biggest insight during this process was the importance of consistent commitment from those who choose to be key team members. The team in New York did everything they could to make the process as accommodating as possible, and seemed to be inspired by my regular participation from Chengdu.

Now that the team in New York have the materials research and a plan of action for manufacture, I’m looking forward to see these projects progress to the next stage.

Keep on top of Thoughtworks Arts updates and articles: