A Continuous Integration Toolkit for Artists

During my Synthetic Media residency at Thoughtworks Arts I began developing a new work Birds of the British Empire that explores the linkages between historical, colonial archives and the training sets used in machine learning. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic the residency took place online via various cloud-based tools and servers.

The museum is… not so much the space for the representation of art history as a machine to produce and stage the new art of today—in other words, to produce “today” as such. In this sense, the museum produces, for the first time, the effect of presence, of looking alive.

— Boris Groys, On The New

Working with Thoughtworks developers we used Continuous Integration (CI) techniques to link together and automate our codebases, so that when for example I make changes to one Machine Learning algorithm the whole system can run end-to-end and generate new results.

These types of distributed workflows open up new ways for artists to organize, store and exhibit work.

A Tool For Artists and Galleries

New media artworks that use machine learning, algorithmic and data-driven processes often require significant hardware resources - computers, graphics cards, power, cooling, etc. Putting these resources physically into a gallery can be problematic. Most galleries do not have the infrastructure or environment to host them, and many do not have staff who are trained to maintain them or diagnose problems when they occur.

As a result, when artists install these kinds of works they come with the expectation of automation, i.e. that the works can run seamlessly without much or any intervention from gallery staff, and that when problems occur the artist can fix them remotely. Coupled with the fact that these are original works, i.e. one-off, unique systems, this is an invitation for new media artwork to present serious maintenance issues for artists and galleries.

| Continuous Integration and GitHub Actions |

|---|

| Continuous Integration (CI) is a software engineering practice in which developers merge their code several times a day on a shared server that continuously monitors changes to the code. CI automates repeated actions such as testing, packaging and deploying artifacts to various destinations. GitHub incorporates a free managed CI tool called GitHub Actions. Using yaml configuration files, a sequence of commands are declared that are triggered upon every commit to the repository. The commands execute the code in the repository, and GitHub provides a user interface that shows if any of the commands have returned errors. |

During the residency we made use of GitHub as a repository for the project’s codebase. Since we don’t have to manage the machines that run the code, it is a really useful and ephemeral tool to continuously build and deploy our changes. It is cost-effective since it is commissioned and decommissioned on demand.

CI and Monorepos relocate most of the hardware and software resources away from the physical gallery and into the Cloud. Cloud-based computers run in dedicated facilities where they are maintained, powered, cooled, backed-up and upgraded by others. This removes this responsibility from the artist and the gallery.

Hosting a work on CI servers provides a way for errors to be automatically identified and reported as soon as they happen. When errors occur or updates are required, the code can be modified remotely without anyone having to be present physically in the gallery.

| Monorepo |

|---|

| A Monorepo is a repository in which code from multiple projects or project components is stored in a single location, such as in a single GitHub repository. This simplifies integration between the different project components. Projects which involve many separate, interrelated machine learning processes ordinarily are separated into different repositories. By putting them into a monorepo, we can run CI via GitHub Actions, test the relationships between the different parts of the project, and make sure the entire project works. |

My residency project involves many separate, interrelated machine learning processes. We stored them in a single Monorepo in order to ease the use of CI and GitHub Actions.

The shift of artworks into the Cloud is generally consistent with the ways in which we encounter and experience digital media today. Streaming media has displaced CDs and DVDs, online storage has taken the place of external hard drives, and ebooks have succeeded print media.

Yet in the case of CI, we take a further step since we are not dealing with fixed media forms. A closer analogy would be to imagine a film still in the editing room being streamed directly to a movie theater. As the edits change so does what is seen in the theater. In terms of a gallery-based artwork this process is not limited to screen-based work. We can envision installation work that receives updates, files, videos, coordinates, audio and other forms.

A Sample Repo

Although Birds of the British Empire is still in development, for this blog post we have created a sample GitHub repo that demonstrates the use of GitHub Actions. The repo can be understood as a framework for any art project that runs in the cloud, yet is exhibited in a gallery. In other words the ‘work’ is computationally based in the Cloud, and physically manifested in the gallery.

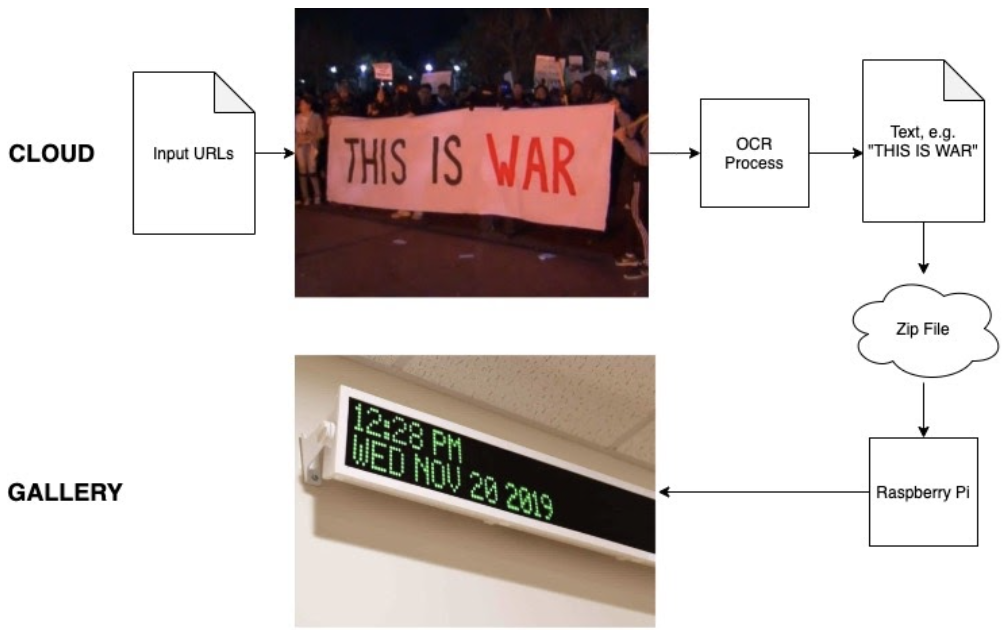

In our demo we have a project that takes online images of protest banners and uses a machine learning algorithm to isolate what is written on them, converting them into machine-readable text. In the gallery there would be an LED message board that receives this text and displays it.

The workflow involves:

- An input file (input.json) that contains some image URLs. In the demo this is simply a list of predetermined URLs, but it would be easy to automatically populate this list via an additional script.

- A Optical Character Recognition (OCR) machine learning process that identifies any text in the images.

- An output file (output.zip) containing the text extracted from the images. And that file is saved to the repo.

- A gallery-side processor (for instance, a Raspberry Pi) that can access the zip file, download it, and then display its contents on the LED message board.

If we shift to thinking of galleries as ‘receiving’ rather than hosting complex new media artworks, then works can be distributed to a larger number of exhibition spaces. Distribution possibilities open up substantially because such works can be simultaneously sent to public spaces, cellphones, television, smart devices, etc. Works can be collected more easily as they effectively exist within repositories. They can be maintained and conserved automatically through the CI’s built-in error checking capabilities, and they can potentially be combined with NFT-style smart contracts. In this scenario, the hardware resources required to run a work can update invisibly in the background, paid for not by the artist or the gallery, but by companies such as GitHub. For artists it becomes simpler to organize, update and version individual works.

The approaches I have explored are specific to my own practice, but I think can also offer a model for other artists working with automated systems-based media. Although the technologies underpinning CI will change, it will not be at the expense of the artist or gallery. Works that run in these environments will, if maintained, be hardware agnostic and run on the latest software and hardware. For example, as GPU processing becomes cheaper and more widely available works can take advantage of this development via CI.

Perhaps one day we will find an exhibition curated through a monorepo with works that synchronize with one another and share metadata. Boris Groys describes the museum as “a machine to produce and stage the new art of today”. I would argue that separating the production from the staging is advantageous to both artists and galleries, bringing us closer to systems shows what the art of today is truely capable of.

Special thanks to Ellen Pearlman, Andrew McWilliams, Rahul De, Anupriya Johari, Carlos Gabriel Gavidia Calderon and Janani Venugopalan for contributing to the development of this project.

Keep on top of Thoughtworks Arts updates and articles: